Existential quantification

In predicate logic, an existential quantification is the predication[1] of a property or relation to at least one member of the domain. It is denoted by the logical operator symbol ∃ (pronounced "there exists" or "for some"), which is called the existential quantifier. Existential quantification is distinct from universal quantification ("for all"), which asserts that the property or relation holds for any members of the domain.

Symbols are encoded U+2203 ∃ there exists (HTML: ∃ ∃ as a mathematical symbol) and U+2204 ∄ there does not exist (HTML: ∄ ).

Contents |

Basics

Consider a formula that states that some natural number multiplied by itself is 25.

-

0·0 = 25, or 1·1 = 25, or 2·2 = 25, or 3·3 = 25, and so on.

This would seem to be a logical disjunction because of the repeated use of "or". However, the "and so on" makes this impossible to integrate and to interpret as a disjunction in formal logic. Instead, the statement could be rephrased more formally as

-

For some natural number n, n·n = 25.

This is a single statement using existential quantification.

This statement is more precise than the original one, as the phrase "and so on" does not necessarily include all natural numbers, and nothing more. Since the domain was not stated explicitly, the phrase could not be interpreted formally. In the quantified statement, on the other hand, the natural numbers are mentioned explicitly.

This particular example is true, because 5 is a natural number, and when we substitute 5 for n, we produce "5·5 = 25", which is true. It does not matter that "n·n = 25" is only true for a single natural number, 5; even the existence of a single solution is enough to prove the existential quantification true. In contrast, "For some even number n, n·n = 25" is false, because there are no even solutions.

The domain of discourse, which specifies which values the variable n is allowed to take, is therefore of critical importance in a statement's trueness or falseness. Logical conjunctions are used to restrict the domain of discourse to fulfill a given predicate. For example:

-

For some positive odd number n, n·n = 25"

is logically equivalent to

-

For some natural number n, n is odd and n·n = 25".

Here, "and" is the logical conjunction.

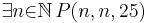

In symbolic logic, "∃" (a backwards letter "E" in a sans-serif font) is used to indicate existential quantification.[2] Thus, if P(a, b, c) is the predicate "a·b = c" and  is the set of natural numbers, then

is the set of natural numbers, then

is the (true) statement

-

For some natural number n, n·n = 25.

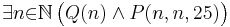

Similarly, if Q(n) is the predicate "n is even", then

is the (false) statement

-

For some even number n, n·n = 25.

In mathematics, the proof of a "some" statement may be achieved either by a constructive proof, which exhibits an object satisfying the "some" statement, or by a nonconstructive proof which shows that there must be such an object but without exhibiting one.

Properties

Negation

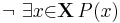

A quantified propositional function is a statement; thus, like statements, quantified functions can be negated. The  symbol is used to denote negation.

symbol is used to denote negation.

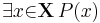

For example, if P(x) is the propositional function "x is between 0 and 1", then, for a domain of discourse X of all natural numbers, the existential quantification "There exists a natural number x which is between 0 and 1" is symbolically stated:

This can be demonstrated to be irrevocably false. Truthfully, it must be said, "It is not the case that there is a natural number x that is between 0 and 1", or, symbolically:

.

.

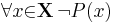

If there is no element of the domain of discourse for which the statement is true, then it must be false for all of those elements. That is, the negation of

is logically equivalent to "For any natural number x, x is not between 0 and 1", or:

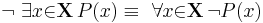

Generally, then, the negation of a propositional function's existential quantification is a universal quantification of that propositional function's negation; symbolically,

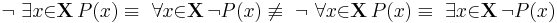

A common error is stating "all persons are not married" (i.e. "there exists no person who is married") when "not all persons are married" (i.e. "there exists a person who is not married") is intended:

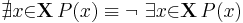

Negation is also expressible through a statement of "for no", as opposed to "for some":

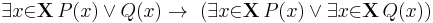

Unlike the universal quantifier, the existential quantifier distributes over logical disjunctions:

Rules of Inference

A rule of inference is a rule justifying a logical step from hypothesis to conclusion. There are several rules of inference which utilize the existential quantifier.

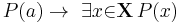

Existential introduction (∃I) concludes that, if the propositional function is known to be true for a particular element of the domain of discourse, then it must be true that there exists an element for which the proposition function is true. Symbolically,

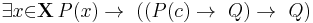

The reasoning behind existential elimination (∃E) is as follows: If it is given that there exists an element for which the proposition function is true, and if a conclusion can be reached by giving that element an arbitrary name, that conclusion is necessarily true, as long as it does not contain the name. Symbolically, for an arbitrary c and for a proposition Q in which c does not appear:

must be true for all values of c over the same domain X; else, the logic does not follow: If c is not arbitrary, and is instead a specific element of the domain of discourse, then stating P(c) might unjustifiably give more information about that object.

must be true for all values of c over the same domain X; else, the logic does not follow: If c is not arbitrary, and is instead a specific element of the domain of discourse, then stating P(c) might unjustifiably give more information about that object.

The empty set

The formula  is always false, regardless of P(x). This is because

is always false, regardless of P(x). This is because  denotes the empty set, and no x of any description – let alone an x fulfilling a given predicate P(x) – exist in the empty set. See also vacuous truth.

denotes the empty set, and no x of any description – let alone an x fulfilling a given predicate P(x) – exist in the empty set. See also vacuous truth.

Notes

- ^ The term "predication" in grammar means the predicate of a sentence which refers to subject and is an adverb or adjective, or equivalent, that describes an attribute of the subject. In logic, "predication" is a declaration (or assertion) that is claimed to be self-evident and can be assumed as the basis for argument.

- ^ This symbol is also known as the existential operator. It is sometimes represented with V.

See also

References

- Hinman, P. (2005). Fundamentals of Mathematical Logic. A K Peters. ISBN 1-568-81262-0.